The Other Mozart

Women aren't allowed to be geniuses.

In third grade, we learned about art from one of my favorite childhood teachers, Mrs. McCullough.

It was also the year I staged a walkout for my class—for reasons I cannot remember. What is seared in my brain is Mrs. McCullough pulling me aside to say she was proud of me for standing up for what I believed in.

I appreciated her so much that I dedicated myself to learning everything I could about artists, musicians, and writers. Every afternoon, I would pull out the encyclopedias (remember those?). Not only would I read about these admired creators, but I would show up every day with a report on the one I learned about the evening before. I’m sure she was delighted with all this extra paperwork!

Names like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Bach, Beethoven, Dickens, Shakespeare, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. They seemed otherworldly to me. Gifted with an ethereal brilliance that transcends time. I also noticed they were all men. Every last one of them.

By the time I reached high school, they had thrown in an Austen and a Virginia Woolf reference, and we even read Little Women. But my childhood grew around stories and art with one kind of history—male.

I believed only men could be geniuses.

It would be decades before I would learn about Mary Shelley, Maya Angelou, Artemisia Gentileschi, Frida Kahlo. Names I learned in my own research. School wasn’t teaching them.

One genius who perfectly demonstrates the erasure of women is Mozart. Not that Mozart, the other one. You’ve probably never heard of her. Her name was Maria Anna Mozart, and she was Wolfgang’s older sister.

None of my encyclopedias mentioned her. I visited Mozart’s birthplace in Salzburg years ago. I understand they have done more to highlight her life in recent years, but when I wandered through that museum, nothing stood out to me that Nannerl (that was her family nickname) was anything more than a sister who helped shaped the genius that was Wolfgang.

Now, this is about the time that some people get furious. “Don’t suggest anyone was more of a genius than Mozart!”

One social media comment from years ago still bothers me. It was a young woman who said, “But Mozart is still a genius.” My fascination/irritation with this comment is twofold. 1. Discussing Maria Anna’s life doesn’t take away from anything her brother accomplished. 2. She used the name “Mozart” as if it only refers to Wolfgang. As if Maria Anna couldn’t even claim her own last name.

You may be surprised to learn that on my platform, I get far more pushback from women than I do from men. But that’s an article for another day.

Seems we all hold the notion that geniuses may only be men.

Wolfgang didn’t simply sit at a piano and begin composing. His natural talent was undeniable. But he was curated, supported, and guided by his father Leopold from the time he was a toddler. Leopold was a court musician for the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, and once he saw his children’s talents, devoted his entire life to ensuring their musical success.

Leopold didn’t begin teaching Maria Anna until she was eight, and it was not with the fervor he did with Wolfgang.

Still, Maria Anna showed signs of brilliance. He taught her everything he knew, taking her on tours through Europe, where she was called “A prodigy.” By twelve, she was playing the most difficult compositions in existence. 1

Maria Anna, in just four short years, developed the talent to overshadow her father, and any pianists in Europe. She wasn’t curated. She had to prove herself.

Compare that to her little brother Wolfgang. Immersed in teaching from the time he could barely talk, watching his older sister’s exceptional talent.

That is the story of women’s history. Maria Anna had to fight for what the world handed Wolfgang readily.

The two toured together, managed by Leopold of course, and Maria Anna often received top billing. Wolfgang was chaotic, charming, rebellious. He lived the part of an artistic genius, wavering between obsession with his music and indulgent behavior. No woman in the eighteenth century would have been allowed this kind of exploration of an artistic life. Maria Anna was compliant, devoted, and agreeable.

Leopold pulled her from performance when she reached “marriageable age.” There were no such limits on Wolfgang. She had to step back and give her brother the spotlight at the direction of her father.

I’m not interested in the conversation about whether we owe Maria Anna some credit for her brother’s genius. I am very interested in discussing how her life would have been drastically different had she been born a boy.

If she did write compositions, none of her music survived. Facts of her life are lost to history—like why she didn’t marry the man she loved, and didn’t marry until her thirties. History didn’t care to document the life of a woman—even a genius.

There are many historians examining if the siblings collaborated on his compositions, but there are only anonymous entries in his notebooks, and letters from him to his sister.2 History didn’t just restrict women geniuses, it actively suppressed them.

I didn't see women artists when I read those books, and so I lived my entire life believing they didn’t exist. This implants an unfair bias in the minds of little girls that they are not capable, not as intelligent, and not worthy of remembrance. I wish I could go back and tell little me about Maria Anna. Whether she was allowed to claim the title of “Mozart” would have been irrelevant. To see a woman called a prodigy, touring the biggest venues in Europe, would have been enough to make me ask myself how big my future could be.

Women’s history means not simply highlighting their accomplishments, but recognizing the societal limitations on their abilities. If Maria Anna was the designated genius, crafted by her father with the intent of professional success, who could she have become?

My passion for history grows from that little girl asking questions about who we are and where we fit in society. That passion continues to branch and spread with every bit of resistance I encounter.

There is space for women in history. It doesn’t erase the accomplishments of men. But it just may ensure that the next little girl sees herself as the genius she could be.

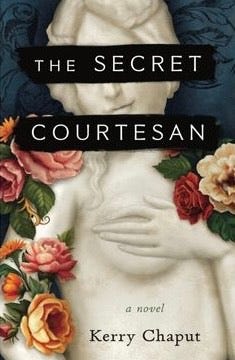

Thank you for reading. I don’t monetize my Substack, but if you’d like to support me, click the link below for suggestions. The best way to support my work is to preorder my book The Secret Courtesan, about women artists erased by history.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/maria-anna-mozart-the-familys-first-prodigy-1259016/

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/clues-in-maria-anna-mozarts-childhood-notebook-17aobe/8161/

Thank you! I went through my younger feminist journey only reading women authors and poets. And I prefer women musicians, especially rock and rollers. Yes, I have wondered who we have missed history (herstory). Rabble on, sister.

Oh how I wish I’d known about Maria Anna when an uncle now deceased, who I didn’t like very much, used to bang on about Mozart. He was obsessed with his brilliance and was a misogynist old bastard. I did the music at his funeral - all Mozart. If only Maria Anna’s compositions had been preserved and replicated the same as her brothers, I could’ve snuck in a final fuck you to him!