The Fossil Hunter Who Survived a Lightning Strike

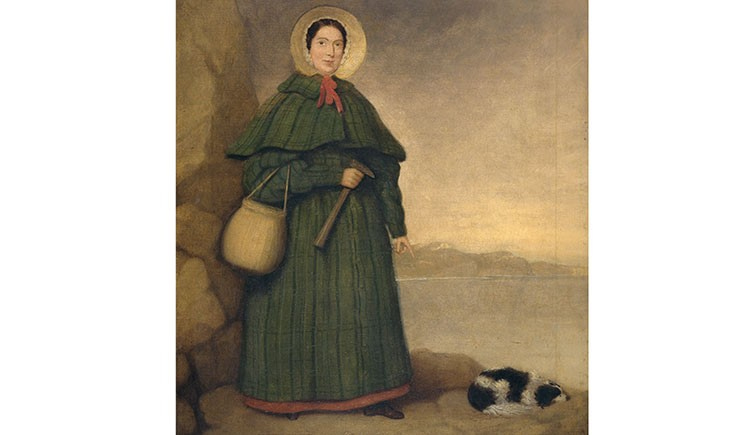

Mary Anning, the woman who changed paleontology

What if I told you some of the most significant geological finds of all time came from an uneducated, impoverished girl from a sleepy English port town?

It’s true, and her name was Mary Anning. With a miraculous start to her life, the girl was struck by lightning at only twelve months old. The woman holding her died from the zap, but little Mary survived. I like to think she had too much work to do here on Earth.

The Jurassic Coast lies on the southern edge of England, holding an outstanding collection of fossils from 185 million years of geological activity. On May 21, 1799, Mary was born in the center of this activity in the town of Lyme Regis.

The family was very poor, and of their ten children, only two survived into adulthood. They lived in a tiny house so close to the sea that flooding was a regular occurrence. Once, the water took out their stairway as they escaped through a second floor window.

Mary spent her childhood collecting fossils along the beach with her father, which he would sell at his cabinetmaker’s shop. By six years old, she was his trusty sidekick. He taught her how to search for and clean fossils. She learned the basics of reading and writing in Sunday school, but Mary received little formal education. She earned her knowledge in bones and rocks collected along the shore, learning geology and anatomy as she went. She would dissect fish to help her understand what she found in fossils and taught herself how to illustrate her finds. Mary Anning may not have had much in the way of opportunities, but her interest and commitment would change the field of paleontology.

Her father died from tuberculosis when she was eleven and she carried on the tradition of selling her curiosities to tourists and collectors to support her family and pay off their debts. She documented and sketched her finds, gaining knowledge with every dig. Ammonites are plentiful in Lyme Regis, and she sold many to wealthy tourists looking for something unique to bring home.

At twelve years old, Mary would make an incredible discovery. Her brother discovered a skull, and she painstakingly dug out a five-meter skeleton (that’s over sixteen feet), which took months to complete. They dubbed it a “sea dragon.”

This was around 1811, almost fifty years before Darwin would publish his work on evolution. This animal was so rare, people thought it was a monster, or that Mary had fabricated the story. It was studied and named ichthyosaurus, which translates to fish lizard. The fossil was so well preserved that fish bones and scales were still visible inside the ribcage.

The fossil fetched twenty-three pounds, and the British Museum later bought it at auction. Male scientists frequently bought specimens that Mary would discover, clean, and identify and, to no one’s surprise, they rarely credited her. The Geological Society of London denied her membership because they only accepted men, a standard that wouldn’t change until 1904.

Mary’s reputation grew. Scientists sought her opinions and expertise.

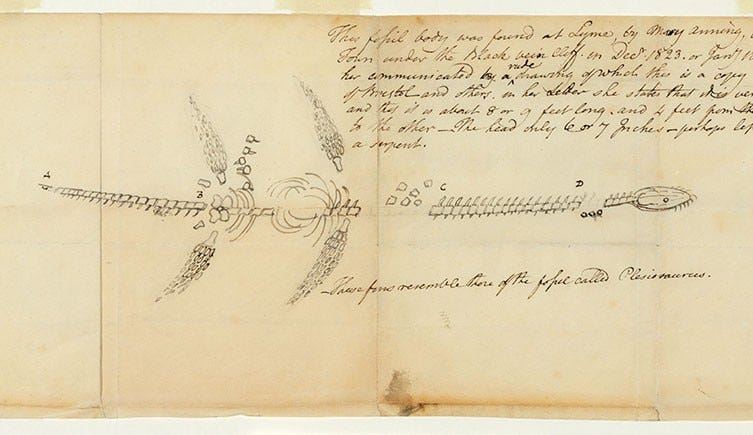

She made another groundbreaking discovery in 1823 when she uncovered a collection of bones with a long tail and wings, exciting scientists from all over Europe at the potentially unknown species. The renowned anatomist Georges Cuvier publicly questioned its authenticity. Certainly, a poor girl from a beach town couldn’t have discovered such a thing. He held a meeting at the Geological Society of London—without inviting Mary—where he confirmed the find, turning Mary Anning into a legitimate fossilist in the eyes of the scientific community.

Mary had discovered the first complete plesiosaur. Up until then, work had only been done on partial specimens.

Later, she found the first pterodactyl outside Germany. At the time it was referred to as a pterosaur. Several of Mary’s finds are considered the holotype, which is the specimen used to describe a new species. Scientists still refer to these specimens today.

In 1829, Mary discovered a squaloraja, a fossil fish thought to belong to a transition group between sharks and rays.

During this time, Mary’s finds garnered so much attention that even major museums struggled to keep up with public interest. Even European nobles held private collections of her curiosities. And yet, Mary still mostly lived in poverty with most of her work uncredited. Without a steady position, she relied on the proceeds from her finds, even opening a fossil shop. While she did have periods with stable income, money remained a battle in her life. Several friends in the fossil world came to her rescue. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch, a close friend with an impressive fossil collection, held an auction to sell many of his finds with proceeds going to help her. Another friend, Henry De la Beche, sold a watercolor of prehistoric animals found by Anning to help her financially.

What Mary accomplished without formal education, support, or guidance is nothing short of miraculous. She gained knowledge and skills commensurate with those of the greatest paleontologists of her time. Her work provided essential knowledge in the study of evolution and the history of Earth. Her contributions were globally renowned, and she pioneered the study of feces, which, though unglamorous, provides invaluable insight into animal behavior and ecosystems. This information became essential to understanding extinction.

Mary died of breast cancer at forty-seven. The Lyme Regis Museum now operates out of her family home, celebrating her accomplishments and continuing the education of fossils. The Jurassic Coast, which Mary played an integral role in, is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The renowned scientist mentioned earlier, Georges Cuvier, was considered the “father of paleontology.” He is credited with the theory of extinction. Mary’s work was vital to his research, though he never credited her. According to one of Mary’s friends, she felt the men of science used her knowledge to further their standings, leaving her behind. She once said, “The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.”

Several fossils were named after her but not until after her death. You can find more information about Mary at the Natural History Museum and the Lyme Regis Museum.

Thank you for reading! Click the button to learn how to support this publication, which will remain free because I believe in making women’s history accessible.

What a remarkable woman! I love her! And of course out of fear and ignorance the men wouldn't give her credit. The male dominated scientific and medical world was full of arrogance (as is a lot of the world now). Of course she persevered as much from need as love of the subject. I can only imagine how excited she must have felt finding these historical treasures. I think it also goes to show that being poorly educated doesn't mean you're ignorant and hands-on, observation can often outdo book learning.

I'm not surprised. We have to work twice as hard, twice as long, to get no recognition.