Elizabeth Jane Cochrane was the most rebellious in a family of fifteen children. What began in 1864 Pennsylvania as a comfortable life supported by her successful father turned quickly when she reached six years old. Her father died, leaving no will for the five children of his second marriage.

Forced to sell their home, Elizabeth’s mother rushed into a terrible marriage. The new husband was an abusive alcoholic, leaving Elizabeth (Pinky was her nickname) desperate for independence and security.

She began school for teaching, one of the few professions open to women in the late nineteenth century. This historical fact always rankles me. Teaching children or nursing the sick, that was for women. Too ridiculous for men to consider, but war was acceptable?

When money for her schooling ran out, she had to return to help her mother. Elizabeth—by this time struggling financially and hell bent on making her way in the world—had fallen in love with writing.

Imagine, she’s now fully entrenched in the struggle of young women with a family to support while the world tells her to simply get married, but she watched her father die and her mother beaten by a drunk who seemed to hate them all. Would you trust marriage as salvation? Me either.

A popular newspaper column spoke of women in the workforce as a “monstrosity,” prompting an angry letter from Elizabeth, who now understood deeply the struggles of working-class girls. The paper appreciated her gumption, offering her a job and assigning her a pen name.

Nellie Bly was born.

Given what we know about her life, what do you think her first few articles discussed? Struggles of working women and advocating a reform of divorce laws.

Let’s take a minute to highlight something important. Her voice got her foot in the door. An angry, spirited opinion that was highly unpopular with men and women alike earned her a spot in a hugely male-dominated arena where she’d be fighting for recognition, against prejudice, and for little money. She stepped out of line, and for that, she was rewarded with a chance. An uphill battle, but a chance nonetheless.

If more women step out of line and pushed against popular opinion, imagine what we could do?

Back to Nellie…

She was an investigative journalist from the start. She tackled difficult, hard to digest stories like the treatment of women factory workers in Pittsburgh. But the newspaper had other ideas. They assigned her the women’s page with stories like flower shows because, of course they did. Ironic that they hired her for her voice then instantly squashed it, right? By ironic, I mean predictable.

She snagged a job as a foreign correspondent in Mexico but returned to be relegated once again to stories on fashion.

Another sidestep here because I’m feeling sassy—Please note that Nellie did not take the job assigned to her, grab the paycheck, and live in gratitude for finding space in a box built for her. When I choose women to highlight for Badass Women in History, I’m looking for women like her, who kept kicking at the edges, pushing and gritting her teeth against every wall built around her.

She quit the Pittsburgh newspaper. Apparently, she left a note on her boss’s desk that read, “Dear Q.O., I’m off for New York. Look out for me. Bly.”

She was about to change journalism forever.

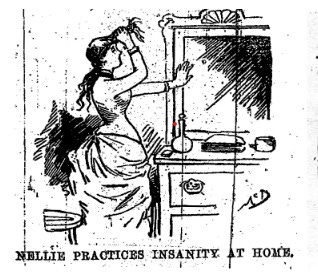

After months of a fruitless job search, she pushed her way into the editor’s office of New York World. The editor could have been annoyed or truly interested, but either way, he gave her an assignment: report on the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. Nellie took it, determined to prove her place in journalism. In 1887, she presented as Nellie Brown who claimed insanity.

She was twenty-three years old.

She duped a judge, the matron of a temporary home for females, and all three top “insanity” experts at Bellevue Hospital to gain admittance to Blackwell Island. She had no way out of this place, putting full faith in her editor and the weight of the newspaper to get her out when her investigation was complete.

Nellie moved about the ward without acting. She spoke to residents and learned the ways of the facility. According to her book, the more “sane” she acted, the more aggressively the staff accepted her as insane.

Side note here, I use the term insane as this was the catch-all for the time. We now have more appropriate and accurate medical terms but those didn’t exist in the 19th century.

As you can imagine, the women who lived here were a combination of those with mental health issues in need of care, as well as young women whose families institutionalized them for a variety of behaviors. Some suffered physical ailments, and others did not speak English and could not communicate their sanity. It was all too common for immigrant and poor women to be thrown in asylums for no real reason.

Injustices were everywhere. Unsanitary living conditions, spoiled food, ice-cold showers, and intense physical and emotional abuse from the staff. Water was undrinkable. They forced the women to sit on hard benches in silence for up to fourteen hours a day, with little protection from the cold.

Their baths consisted of buckets of cold water, repetitive use of filthy facilities, and reuse of towels used on those with skin conditions and weeping sores.

Nellie astutely noted that these conditions would make any woman, mentally ill or not, lose their sanity.

When the paper rescued her from the asylum after ten days, she had a wealth of shocking information to write her articles. While relieved, Nellie could not take the suffering women with her back into the free world. She knew this article had to make waves to protect those locked away and abused.

New York World published her two-part series “Behind Asylum Bars,” which included illustrations and garnered shock from readers. Concerned citizens flooded the asylum with complaints and put pressure on them to reform their practices. Her reporting gave her a permanent position on the paper and led to a book titled, “Ten Days in a Mad House.”

Her bravery and writing brought about asylum reform, as well as forever changing the field of journalism. The budget for these facilities was nearly doubled, and an extra fifty-thousand dollars went specifically to Blackwell, which closed seven years after Bly’s story was published.

That isn’t the end of her incredible story. In 1889, she set out to travel the world in eighty days, but through the use of steamships, trains, rickshaws, donkeys, and even an elephant, she completed it in seventy-two, setting the new record. She sent dispatches of her travels back home where multiple papers published the young woman’s adventures, which included visiting a leper colony.

After her husband passed, she ran his manufacturing company and received several patents as an inventor. She returned to reporting during WWI, becoming one of the world’s first female war correspondents. She wrote from the Eastern Front, detailing the realities of trench warfare.

She died of pneumonia at the age of fifty-seven.

Nellie Bly

1864-1922

Please enjoy my fictionalized short story companion piece:

Asylum Shadows

Nine days ago, they escorted me through the octagon and inside a set of double doors to this place where the sun does not reach and the air stagnates around frightened women with frenzied eyes.

A broken slab of plaster exposes the wooden lath underneath. Like chasing clouds, this hole turns into different shapes as the day ticks on. What began six hours ago as an elephant with a short trunk and a vase of dead flowers has now presented as a demonic smile with missing teeth.

A Canadian goose honks his way past the building, not that I can see it. We aren’t permitted to face the window. Too much hope rests in that view.

My backside burns from the hours spent on this hard bench. Don’t wriggle. The staff doesn’t permit us to move. The immobile and sedate are easier to control. At the end of the bench, a girl no more than sixteen picks at sores on her face. Her trembling fingers are no match for her whimpering which makes me want to wrap my arms around those bony shoulders. The damn sounds in this place.

“Girl,” a nurse shouts as she looks up from the glossy pages of “Good Housekeeping.” The put together woman in a white uniform rolls her eyes. “Shut the hell up.”

“I can’t.” The girl rocks, her foot shaking in place. “Make it stop!” Her eyes meet mine. “Please make it stop,” she pleads, on the verge of weeping. She slithers to the ground, tightening into a ball of bones and pale skin. I swallow the desire to drop next to her and wrap her in a hug.

The nurse presses her tongue to the roof of her mouth, her impatience brewing like a storm. She slaps her magazine on the table next to her coffee and drags herself toward the crying girl who now yanks at her hair and babbles incoherently.

Incurables, they call them. The ones who need help and live in the hell of their terrifying mind or inefficient bodies get relegated to Welfare Island, otherwise known as Blackwell. Among the penitentiary and workhouses rests the Women’s Lunatic Asylum that currently holds me in its walls. Away from the city, the undesirable and unfit languish at the hands of nurses and doctors who treat them as filth.

Without realizing, I’ve shifted forward, turning away from the menacing plaster shapes, my body poised to pounce. I may not belong here, but to them, I am undesirable, just like the rest of the women.

“You,” the nurse barks at me. “Turn around before I slap that smirk off your face.”

I slide back, closing my eyes to avoid watching yet another woman slapped and dragged away. I wish I could shut down, close my eyes. But I need to see every detail and mark it to memory.

Nine days ago, a judge ordered me into the Women’s Lunatic Asylum after I presented a convincing case to those in charge of vulnerable women’s futures. If a fully sane reporter can manipulate the top insanity specialists with little more than a few nights practicing in the mirror, what good are experts at all?

The girl’s whimper indicates the nurse has grabbed her arm. Don’t look, Nellie.

I haven’t been here long enough for them to break my humanity, so I risk another glance. The nurse drags the girl across the floor by her arm. She doesn’t seem to notice the red marks building under the nurse’s fingers as she’s lost in a panic state, eyes shut tight, screaming, “Get out of my mind, you bastard. Get out! Get out!”

Her frail legs drag across the hard tile through a puddle of urine from the group tied together with ropes and sedated with some kind of medication that keeps them detached as zombies.

The food turns my stomach and the hollow gaze of women around me pecks at my every desire to flee. I can’t, and not just because I’m at the mercy of the wardens, but someone needs to tell this tale. Someone must expose what happens on this island. This assignment is my chance to prove I deserve a spot in journalism. No more flower show stories and fashion opinions. When New York World’s editor shared this proposition, I agreed without hesitation, ready to take on any challenge. I had no idea what awaited me in this hospital of horrors.

The nurse kicks the door with her foot, banging against the wall as they struggle into the hallway. The break in supervision causes a collective sigh from the bench. I look around, memorizing every detail of the horrid room. The smell of body odor and ammonia. The woman in the corner with a hole in her gown exposing her breast. The gaunt cheekbones and mold that climbs from the corner where a leak drips down the wall.

“They’ll strap her to the bed until the episode passes,” a soft voice with an Irish lilt says from beside me.

I turn to her, startled by the clarity in her blue eyes. I’ve grown so accustomed to blank stares. Her hair, short and orangey-red, frames her soft face. She must be new, like me, as she hasn’t taken on the sallow hue of most women here. Shockingly, she’s lucid. I can tell from the way she speaks to me rather than at me.

“Will they hurt her?” I ask.

“Yes.” Her shoulders rise toward her ears. “It’s best to stay quiet and never make eye contact.”

A sharp draft creeps in through the windows behind us, slamming our necks and arms with cool air. “They could turn even the most well-adjusted woman into a wreck with only one day in this place,” I say with a shudder. “I’m horrified.”

The brightness in her cheeks fades as her shoulders sag. “This is who humans become when no one is watching.”

When I prepared for this assignment, I remained convinced the rumors were exaggerated. How can doctors treat those in need with such disregard? Now that I have seen their evil eyes, their satisfaction with power over these powerless women, I have my answer. Because they can.

Everyone stretches, rubbing their backsides and enjoying the few moments we aren’t threatened. “You seem perfectly well,” I say.

She scans me head to toe, seemingly grateful for signs of life. “As do you.”

I shouldn’t tell her the truth, though I long to. “The doctors seemed convinced of my insanity.”

She nods in understanding. “My father admitted me.”

With only a few minutes to get the details of her story, I push farther than what feels comfortable. “For what reason?”

“If you ask him, it’s because of my immorality.” She dips her head to the side, eyes focused on mine. “He caught me kissing the boy next door.”

“Certainly, that isn’t reason enough to commit you.”

“I’m one too many people to manage since my mother died, and seeing as how I refused marriage, he lightened the load. Two of my brothers went to an orphanage. He kept my younger sister so she can cook and clean.”

My stomach turns. I know all too well how some parents die, and others turn to desperate means. “Incredibly unfair.”

“Yes, well. I’ve committed the worst sin of all.”

I rub my backside. “What is that?”

“Poverty.”

Three nurses burst through the door just as I whisper to the woman, “My name is Nellie.”

She smiles. “Katherine. You can call me Kate.”

One bright moment may be enough to sustain another miserable night in the asylum. I reach for her hand and squeeze, hoping to hold on to her for a bit longer. But the nurses kick the benches, rattling them against the floor to force us to stand.

“Bath time,” the one closest to me says.

The worst of all times of day has arrived yet again. We form a line as a large rat scurries across the floor and through a hole in the wall.

How long have they been living like this while we go about our lives outside in the sunshine with laughter and easy conversation? The answer, I know, is too long.

***

My wet hair dampens my pillow. I try to dry my face with the scratchy flannel gown they shoved on my damp body after dumping frigid water over me until my teeth chattered. They call it a bath but it’s really ice-cold torture to force compliance. They enjoy watching us tremble.

I stood there covering my naked body, arms wrapped around me as my hair dropped streams of water down my back. “Why don’t you supply towels?” I asked.

“This is charity, miss,” she hissed. “Be grateful you get anything.” Her rough voice sandpapered the air near my ear.

And here I lie, shivering and wet, staring at the ceiling and tracing shapes from the shadows streaming through the bars. Mr. Pulitzer should break me out of here tomorrow. Ten days was our agreement. I asked the doctor today if I could leave and he said only, “Your belief that you are fine is proof why you need us.”

A terrifying thought grips me and slams the breath against my chest. What if my editor can’t release me? The shadows move, undulating like water into the moonlit figure of a spider, just like the one I found in my bread at dinner.

***

I look the other way when they serve boiled meat that exudes a sour smell. The water in the drinking glass is cloudy with a hint of yellow. The rest of the women devour the food, so hungry they don’t hesitate.

We’ve already cleaned the nurse’s quarters and laundered their clothes. Free labor as they slowly siphon our faculties under the guise of order. I am unwell after only nine days. What have months done to the others? Did they begin like me?

I don’t know the time, but every minute that passes, I wonder if I’ll be here another day, another month. A woman in a wheelchair reaches for her food but her hand jerking causes her to spill food onto her lap. A nurse stands over her watching.

I slide over to her. “Let me help you.” I reach for the spoon, but the nurse slaps it from me.

She grabs my wrist. Her pinned hair and fresh face are so at odds with her sour demeanor. Anger oozes from a face too young for such hardened lines. “She must learn to do it herself.”

“She can’t.” I motion to the poor woman. “Look at her. She’s hungry.” The woman has an open mouth, almost as if reaching for the food in her mind.

“And that is why you incurables will never get better. Always looking for sympathy.” She yanks my collar and shoves me back into another woman who spills her soup and begins to scream.

“Now look what you’ve done!” The nurse grabs me again, but not before I shove a spoonful of clotted soup into the patient’s mouth. I lock eyes with Kate, who seems to read my mind. She’ll help her eat while the staff deals with me.

Two nurses or orderlies—I can’t ever tell who is who—restrain me to a chair and toss a glass of water onto my face. I catch my breath, looking to make sure Kate has helped the woman eat. She’s wiping her chin. I worry she’ll be tied up next.

“Cold water does wonders to stimulate the nervous system,” a man says. He grins at me. A sinister smile to reveal what I already know. He finds joy in demeaning us.

“I don’t belong here,” I say.

He laughs. “No, doll. No one belongs here.”

The truth does little to soothe me. I may rot in here forever at the hands of people who see us as degenerates. Worthless women who failed at the expectations of life. “You don’t need to be cruel. We’re just people who need help.”

I know this will enrage him.

He bends down, eye to eye with me. “We don’t owe you kindness. You need boundaries.” He licks his palm and swipes it down my cheek. I don’t wipe away the filth, as he may do worse. So I stare ahead and shove down the embarrassment that floods my body. “You’re dangerous.” He shoves me sideways, nearly knocking the chair over with me in it.

My danger rests in the power of my words which, for the moment, remain locked in my mind, plotting. I’ve already crafted much of my article in my head. “Behind Asylum Bars.” Now that I know how they imprison and abuse those in need of help—poor women, immigrants, and anyone without resources to protect them—I will make sure the world knows too. One day, he will remember me. He will see my face in the newspaper and remember the journalist he spat on.

The room watches me. The usually vacant eyes turn alert when they target one of us. Like a beehive, they go on alert when one braves our predator. What thoughts do they hide from the staff, and what dreams still thrive in the recesses of their mind? What began as a story for me has become about them, these hollow faces and broken lives.

His face tightens, egging me to respond. I turn my eyes to his, wiping my shoulder across my cheek without any show of the disgust that seethes inside me. I don’t cower. I don’t flinch.

Just as I’m certain he’s about to release his wrath, the doors slam open and a man bursts through the door, the matron on his heels. There’s a collective gasp from the women labeled as lunatics. This man doesn’t belong in this place, and we all know it.

He waves a stack of papers. “I am Peter A. Hendricks, lawyer for New York World. I am here to demand the release of Nellie Brown.” A cover to hide my pen name.

I stare right at the orderly. “I’m here.”

“Untie her this instant.” Mr. Hendricks slaps the papers on his palm. “Before I have you all hauled into court.”

They hesitate. The orderly puffs his chest, stepping closer to Mr. Hendricks, as if he could stop the force of a lawyer with his brute strength. “Who do you think you are?” he spits.

“I am the law, and you don’t want to upset the newspaper who has the power to expose your name, your title, where you live—” He shoots a glance at me, grimacing at my wet face and mussed hair. “And how you’ve treated our staff.”

The orderly cracks his knuckles, but the matron raises her hand to control her staff. “That’s enough.” He steps back, but not without the darkest grin aimed straight for me. I’ll remember him.

A doctor who stood silently while his staff restrained and humiliated me walks up beside the matron. “We will comply. Release her.”

They untie me. I stand and dust off the droplets of water and bits of food before clearing my throat.

“You’re a journalist?” the doctor asks before swallowing hard.

“I’m not just a journalist,” I say, lifting my gown’s sleeve to scrub my cheek. “I’m the woman who will make certain you all pay for what you’ve done.”

I walk in step with the lawyer, grateful beyond words that Mr. Pulitzer kept his word. On the way out, I stare at Kate. I hesitate. Can I swoop her up? Take her with me? She shakes her head, seeming to know what I’m thinking.

A smile tugs at her lips. It may be only days until those rosy cheeks lose their glow. “Do some good out there, okay?”

Mr. Hendricks elbows me. “We must leave now before they give us a fuss.” I nod. I lift my hand, a hopeless goodbye to Kate who slips another bite of bread into the woman’s mouth. We leave the dining hall and walk through the corridor, right into the sunshine.

“Let’s get you home and cleaned up,” he says, both proud and trying not to grimace at my oversized gown and stocking feet. “I’ll have your things sent to your apartment.”

And just like that, I’m free. Because a man broke me out. Because I have access to money and an editor who needs me. My ribs tighten against my trunk, as if I can harden myself and protect my heart from what I now know. I can’t. All I can do is remember these women and do something to free them from this hell.

I glance back at the windows of the asylum that abused me for ten days. These walls shut in lost souls and break them down minute by minute to ensure they lose their minds in a maze of endless despair, like rats in a barbed wire trap. The world of insanity was easy to enter but impossible to leave.

Written by Kerry Chaput

Edited by Sayword B. Eller

I've always loved Nellie Bly's story, so thank you for this.

Have you ever seen Drunk History's take on her story? Laura Dern played Nellie....

Wow, such an amazing story! Thank you Kerry, for continuing to share these wonderful women.